It’s not the heat; it’s the existential dread

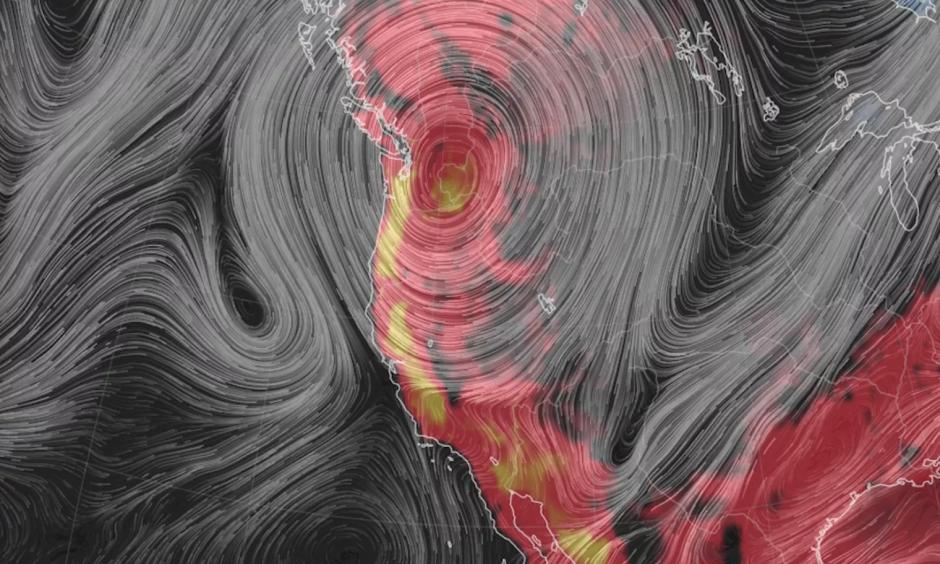

The most severe heat wave in the history of the Pacific Northwest and Canada gripped the region in all-time record-breaking triple-digit heat at the end of June. The heat wave was due to a major heat dome, or sprawling zone of high pressure, and bulging jet stream that sent hot air flowing into the region for several days. Both the record temperatures and record-strong high pressure system have strong ties to human-caused climate change. (Source: Climate Signals)

In an article in the Washington Post entitled ‘It’s not the heat. It’s the existential dread‘, Charlie Warzel reflects on the heat wave in the USA and in the Pacific NorthWest where he lives.

He writes:

All this record-breaking has fed another sensation just as oppressive: a lingering existential dread about the future. There is a sinking feeling that has accompanied the heat; there’s a distinct psychological pain that accompanies the thought that the unbearable present is only a preview of the extreme climate to come.

It’s not hard to imagine what comes next. And that’s what makes it so horrifying.

The phenomenon of climate anxiety has sharpened for many over the past few years. In a poll from October, 55% of respondents said they were “somewhat or extremely anxious about the impact of climate change on their own mental health.” People who had been insulated from the disastrous effects of warming – thanks to geography, or privilege, or both – are newly confronting this uncomfortable reality in their daily lives.

Britt Wray, a postdoctoral fellow at Stanford University and the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, writes about climate anxiety and grief in her newsletter, “Gen Dread.” She explains that the field of mental health is now scrambling to develop tools for people struggling to coexist with this existential threat. One strategy, Wray says, is finding ways of embracing and accepting that distress, rather than pushing it away.

It feels unfair to come out from pandemic lockdowns and confront yet another crisis that requires reserves of resilience. But Wray argues that squaring up to your anxiety and dread around climate change “gives you resources to draw from and ultimately makes intense moments like this heat wave easier to bear.”

“If we can acknowledge our feelings and bear the fact that we’re faced with extremely difficult truths about the planet, we can use that to gather strength,” she said. “This is not easy. You need to know you’re not alone but also know that you’re not going to find a silver-bullet solution.”

One of the most important things we ought to be doing, according to Wray, is talking about the climate crisis honestly in our everyday lives, with our friends, family and colleagues. “We can’t just do it when there’s a heatwave in our neighbourhood. We need to weave it into our social fabric,” she said. It won’t be comfortable, but it will reflect the urgency of the moment we’re all living through. And this small piece of common ground is critical if we hope to address this emergency.

Talking about our shared dread won’t bring down the temperature or vanish the smoke, but leaning into the grimness is grounding – because a dystopia feels only more dystopian when everyone’s trying to pretend things are fine.

(Published in the Washington Post Opinion by Charlie Warzel on June 29, 2021. He is a journalist who writes “Galaxy Brain,” a newsletter about technology, media and politics)